It is hard to imagine an activity today that isn’t tracked in some way. On any morning your phone can likely tell you exactly when you woke up (and how far you were from hitting your sleep goal), the number of steps you took to reach the kitchen, and where you are most likely to go when you leave the house. The articles you skim and the emails you open all track, to the microsecond, how long you paid attention to them, and every app knows how long you doom scrolled. Before you have even finished your cup of coffee, you have already generated dozens of data points, to be sent to dozens of servers and analyzed to provide greater opportunities to collect more data.

This isn’t an article on the dangers of living in a surveillance state though, or the evils of big tech (we’ll do that later). Data is everywhere and what we can do with it is, for the most part, great. But when data becomes private data, the stakes for companies collecting or storing it rise exponentially. And the transition to handling private data may go unnoticed for small companies. For example, the small florist modernizing their cash-only point-of-sale system to an all-in-one Square terminal that accepts credit cards and Apple Pay. The growing regional distributor overhauling its sales process from a two-decade old excel spreadsheet to a HubSpot integrated workflow. The Etsy seller expanding her offerings to include personalized wares. This article is about the little guy who wrongly thinks “I don’t have to worry about privacy laws because I don’t collect any private data.”

What exactly is private data?

Data is any collection of information that can be used to make decisions or solve problems. It can be numbers, words, images, or audio, and can be organized into databases or dumped in the intern’s inbox like the drop-off pile at the Salvation Army. If you ask your customers a question, the answer is data. If your customers click a preference box, type a caption, log a result, upload an image, provide a payment method, or even open an email, you are generating data. Data is everything useful on the Internet and often an unbelievably valuable asset for a business.[1]

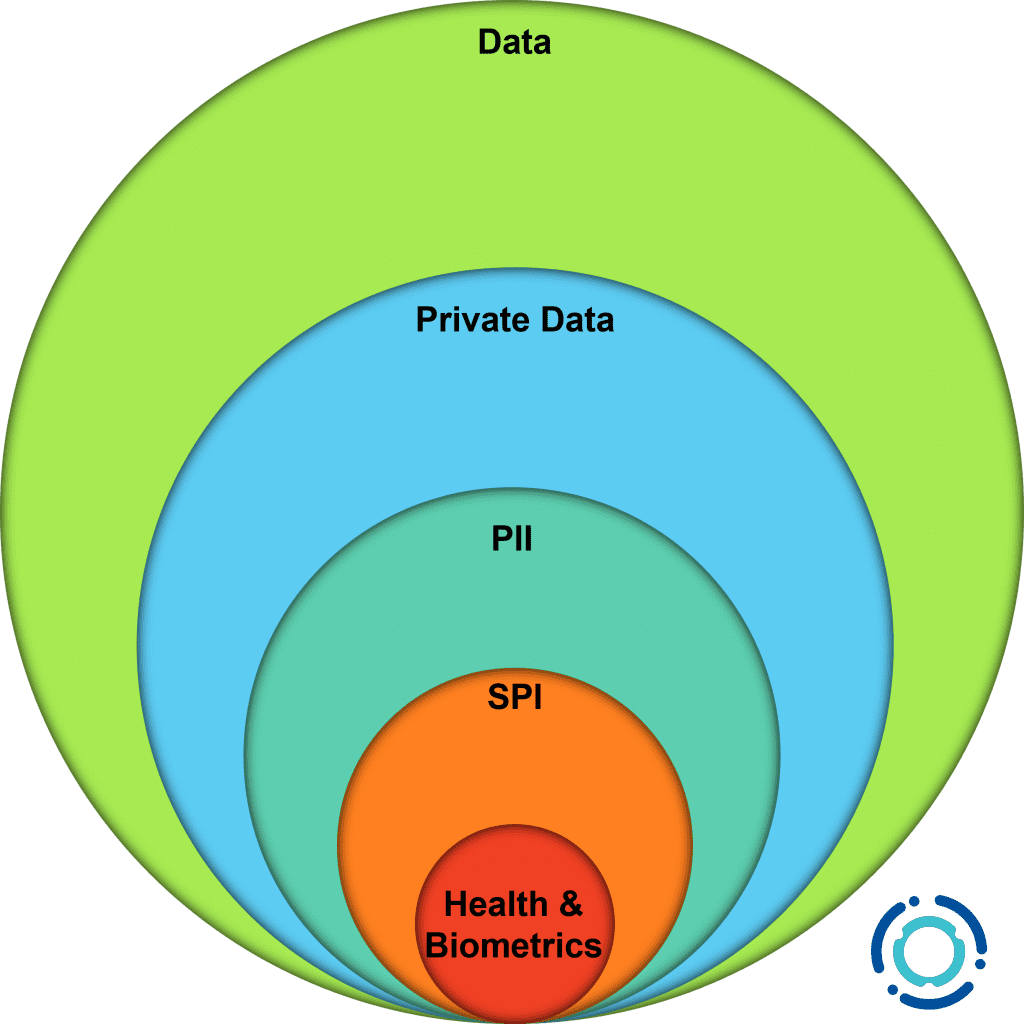

When data can be used to profile or identify an actual person, it becomes private data. This may take some imagination, but if you can aggregate a step counter that measures stride with a coffee loyalty program purchase, it’s possible to identify the only 6’4” person within the quarter mile radius of the coffee shop who makes that purchase each day. Add in more data aggregation points and it is easy for someone to feel watched, tracked, and targeted in their “non-online” activities. Usually, private data is more expansive than personally identifiable information (PII) which more directly identifies someone using classic distinctions (name, age, date of birth, address, phone number, etc.). As technology rapidly expands, the types of tracked and stored data that can reasonably be classified as private are likely to expand as well.

PII may be collected in very straightforward ways. A name, phone number, address, and credit card information are collected to conclude a purchase or schedule a service. Within PII there is Sensitive Personal Information (SPI) which includes account numbers, social security numbers, driver’s license numbers, religious affiliations, race, gender, creed, or immigration status. SPI is most often collected to prove identity, age, or status. Within SPI is a category of medical and biometrics data collected as part of authentication, diagnostic, aesthetic, or self-improvement services. [2]

PII may also be collected in less obvious ways. A custom plaque that commemorates a birth date, complete with full name, and a location. A coaching app that asks for written or recorded accounts of customer milestones and setbacks. A personalized time management service that tracks locations, minute by minute, and collects data to present to the client.

When businesses are managing this type of data, the rules on how to handle it may be less clear cut. And when customers are providing it, they are far less likely to recognize the information as private than they would be if a business were asking for their social security number. What harm does there seem to be in an app that can tell them the last 10 restaurants they visited, show them how a pair of sunglasses would look on their face, or let them order coasters to commemorate the birthday of their best friend’s baby?

Data privacy laws are evolving, and in areas where the laws are unclear, you may face significant customer backlash if data is mishandled, regardless of where the law stands.

Wait, my name and phone number has been published in a phone book for decades, why does everyone now care to keep it private?

Remember when your house had a phone? And calling a home phone number was a game of conversation roulette, since everyone in the house had equal rights to that number? (No? Oh, neither do we.) Today, most individuals use a cell phone as their primary phone number, and a growing number of households no longer have a landline or any other version of a ‘home phone.’ Since online security has embraced your cell phone as your identity for many multi-factor authentication tools, your phone number has become one of the main corroborating data points to verify your online identity.

Other pieces of unique information about you can be used in similar ways. Your birth date, address, relatives’ names, license plate, and many other data points can be used to impersonate your identity or otherwise compromise your security and privacy.

A computer doesn’t differentiate between the bytes that it creates, processes, or stores. But hackers do. Hackers know the with the right aggregation of information they can instantly impersonate someone’s identity to open a credit card, buy a house, and swindle a business out of profits. Hackers know how to exploit weak identity and authentication systems to change their identity in under a second and how to build databases of stolen information to have at their disposal.

To combat this threat, parts of the world have decided the most efficient way to thwart attackers is to ensure that everyone who collects PII collects this information only when needed and consented, securely stored, used appropriately, and removed when no longer needed.

Isn’t data security the responsibility of the web app or service?

Yes. But the web app didn’t collect the information, can’t control how you use it, and won’t force you to remove it when you no longer need it. This is where the parallel paths of privacy and security diverge. It is a web app or service’s responsibility to keep the information secure. It is the data collector’s responsibility to keep the information private. This means that the company that aggregated and mismanaged PII cannot escape their responsibility for a data breach merely because the information was breached due to a 3rd party’s poor security. A victim who had their PII stolen may argue that their sensitive data was only put at risk because of the misuse of the company that collected the information.

How do I keep my customer’s private data private?

There are a few basic principles embedded into virtually every regulatory and statutory privacy scheme:

- Only collect the information you need

- Only use the information in the way your customer consented

- Encrypt your customer’s data at rest and in transit

- Restrict access to customer data to only those who need it

- Delete data when it no longer is needed for the original purpose

The first step, of course, is looking closely at your business needs and practices to determine exactly what data you are collecting, what you are using it for, and how you are handling it during that process. A thorough mapping of your business practices can help you pinpoint the issues you may have and help you identify areas of data collection or handling that you hadn’t previously thought about.

If your business collects payments online, the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standards are a good place to start. If you are handling payments yourself, this is on you. While many small businesses go through other companies for payment processes, those who do should still be aware of the ways their own systems and records could be incorporating customer payment data. They should also, despite the temptation to leave it all to someone else, ensure they are cognizant of the way any other company they associate with handles their data. With regulatory notification requirements measured in hours, the day of a breach is not going to be the most convenient day to start asking your vendors, and your customers will expect answers.

[1] Companies must not only look at the data they intentionally collect, but also the data they unintentionally collect. Any open text box can be used to type in a social security number, or a blog comment can reveal sensitive health conditions. As a business owner, you are responsible for the data you collect, and save, regardless of your intent.

[2] For simplicity, this article focuses on data provided by consenting adults. When data concerns persons under 18 or worse, under 13, all data should be considered SPI by default with consents needing to come from guardians. The tricky part is you first must collect SPI (the user’s age) before you can figure out if you should even collect the SPI information. This requires good, immediate, and permanent data destruction practices baked into the data collection workflows.